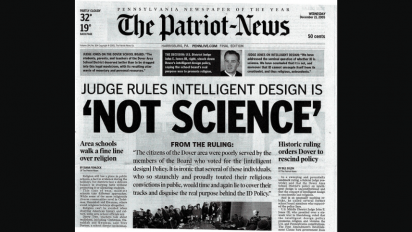

After the Dover Area School Board adopted a policy in 2004 requiring that “Students will be made aware of gaps/problems in Darwin’s theory and of other theories of evolution including, but not limited to, intelligent design,” and subsequently attempted to require its ninth-grade biology teachers to read a statement commending “intelligent design” and the “intelligent design” textbook Of Pandas and People to their students, eleven local parents filed suit in federal court, in what would become known as Kitzmiller v. Dover.

What was primarily at issue in the case was whether the board’s actions violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. The plaintiffs argued, and the court agreed, that the relevant tests of whether the board’s actions were constitutional or not were the endorsement test, articulated in the Supreme Court’s 1984 decision in Lynch v. Donnelly, and the earlier three-prong Lemon test, articulated in the Supreme Court’s 1971 decision in Lemon v. Kurtzman.

In the endorsement test, the question is whether a reasonable objective observer familiar with the relevant facts would consider the challenged actions to have conveyed a message of approval or disapproval of religion. Examining both the board’s claims about “intelligent design” and about “gaps” and “problems” in evolutionary theory, the court concluded that the answer was yes: both members of the community and students in Dover’s public schools would have understood—and did understand—the board to have been endorsing a religious view.

In the Lemon test, there are three questions, relating to purpose, effect, and entanglement, but entanglement was not relevant to the case. So the questions were, first, whether the board’s actions lacked a secular purpose, and, second, whether the principal or primary effect of the board’s action was to promote or obstruct religion. In a lengthy discussion, the court found that the board’s actions were clearly motivated by a desire to promote a particular religious view and described “[a]ny asserted secular purposes by the Board” as a “sham.”

The court’s discussion of the effect test was substantially briefer, because the relevant issues were basically the same as for the endorsement test: the court wrote, “we will incorporate our extensive factual findings and legal conclusions made under the endorsement analysis by reference here.” The result was the same: “The effect of Defendants’ actions in adopting the curriculum change was to impose a religious view of biological origins into the biology course, in violation of the Establishment Clause.”