I have often insisted that there is no one argument that by itself makes the case for evolution. Rather, it is the consilience of many diverse arguments all leading to the same conclusion that makes the case.

But the article by E. E. Max, "Plagiarized Errors and Molecular Genetics" in Creation/Evolution XIX, comes closer than any to making the case all by itself. It is especially nifty for two reasons: (1) the evidence establishes the common ancestry of humans and apes, which is the antievolutionists' biggest stumbling block, and (2) the article establishes parallels with legal cases in which plagiarizers were convicted. This is nice because lawyer Norman Macbeth, in "Darwin Retried," suggests that the case for evolution would not stand up in court.

The article did have a few loose ends which I wonder if Dr. Max would tie up: (1) For the reason indicated, it would be nice to have citations to the two legal cases he describes. (2) It would be nice to have a quantitative comparison of nitrogen base pairs shared by the epsilon gene and its classical pseudogene, which establishes their common origin, and the same for various other appropriate comparisons. Calculations of the probability of such similarity arising by chance would be useful and could be compared with typewriting monkeys and hurricanes going through junkyards. (3) The test proposed by Frank Awbrey (?) should be performed: if pseudogenes are functionless, and if they've existed long enough, the rate of occurrence of substitution mutations should be as great for the first two nitrogen bases of each codon as for the "wobbling" third one. (4) Finally, several other kinds of evidence, all of which point to humans and chimps having shared a common ancestor more recently than either shared one with gorillas, lead me to conclude that there must be some other explanation for chimps not having the epsilon classical pseudogene. Is loss of it through a deletion mutation a plausible explanation?

Karl D. Fezer

While reading Dr. Max's article, "Plagiarized Errors and Molecular Genetics," I found myself thinking, "Of course! Why didn't I realize that?" It seemed to me to be of that kind of information that lies around under your nose for long periods of time and seems retrospectively obvious once someone points it out.

I want to share with you the pathway of my thoughts concerning a creationist response.

For decades, young-earth creationists have rejected all the evidences of an ancient Earth yet have retained (contradictorily enough) the apparent age argument: "None of the so-called evidences of an ancient Earth really prove that the Earth is more than several thousands of years old; but even if they did, the only reason for this would be that when God created the world several thousand years ago he created it with the appearance of having been around much longer." So, if the evidences of an ancient Earth are mistakes, the Earth is young. If the evidences of an ancient Earth are real, the Earth is young. You just cannot beat the simple (il)logic of creationists.

I believe that this is probably the form of argumentation that will be used against the evidence for evolution that is implied by genetic errors. In fact, ancient-Earth creationists have already argued in such a manner concerning evidences of organic evolution. "As God created each new animal kind over the ages, he could have created each one in such a way that it possessed the appearance of having evolved from some previous kind." And in this specific case, genetic errors are one of those "created appearances" and thus do not constitute a real evidence of evolution.

I will now (sigh) leave this realm of theological fantasy and enter reasonable discussion.

Dr. Max states very briefly (and shows in Figure 3 of the article) an observation that I found intriguing. He says that the processed pseudogene is found in humans, gorillas, and chimpanzees (and also several monkey species). Then he states, "[The classical] pseudogene is . . . shared by man and gorilla but is not found in other apes or monkeys." I see two possible indications from this: (1) humans and gorillas are more closely related than humans and chimpanzees or (2) humans and chimpanzees are the more closely related species, but the classical pseudogene under scrutiny has suffered deletion in chimpanzees' genetic material. I have two related questions: is the second situation that I have just stated really a possibility, and, if it is, how is it possible to determine that such is the case?

Finally, since anthropological thinking has for a long time considered chimpanzees to be, of all the apes, the most closely related to humans, would Dr. Max please elaborate on this point?

I want to thank Dr. Max and you for this article. I enjoyed it much.

Todd Greene

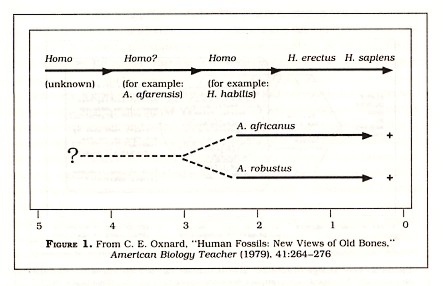

Martin Nickels' article "Creationists and the Australopithecines" (Creation/Evolution XIX) very astutely points out the dishonesty of creationists such as Gish, Kofahl, and Morris. Nickels did an excellent job showing how these individuals distorted Oxnard's work on the locomotor functions and evolution of the australopithecines. It should be reiterated that, in Nickels' article, Oxnard's position on the evolutionary lineage of the australopithecines applied only to the forms Australopithecus africanus and Australopithecus robustus and not to Australopithecus afarensis. In his 1979 paper, however, Oxnard explicitly refers to the "new fossil finds" (A. afarensis) of Johanson and others. He identified this material as humanlike and placed it on the ancestral line of humans, assuming an intermediate status. While he classified afarensis as Homo, he stated that it will probably remain classified among the australopithecines (see Figure 1). So, while Oxnard still maintains a separate line of hominid evolution for A. africanus and A. robustus, he quite clearly places A. afarensis ancestral to Homo sapiens.

Despite it all, however, I'm sure the next time I read or hear a creationist talk about human evolution, Dr. Charles Oxnard will have established that the australopithecines did not walk upright and were not intermediate between ape and man.

Michael L. Bagby

My understanding of professor Geisler's design argument (Creation/Evolution XVIII) is as follows:

- Certain objects (the faces on Mount Rushmore, books, watches) possess a complex structure which is obviously the product of intelligent manufacture. Intelligent action is necessary for their existence but needs not be a direct cause (consider an automated assembly line). Call these artifacts class "A" objects.

- The structure of DNA is mathematically similar to class "A" objects. The two have the same type of complexity.

- Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that the information content of DNA originated by intelligent action (by God, gods, genetic engineers from planet X, super-robot from a deceased civilization, and so forth). As DNA is identical to an "A" class object (with the exception that it lacks the signs of manufacture as we understand it), it should be included in the class of objects which have an intelligent origin, class "I" objects.

I trust I have not unduly oversimplified the argument, but the above does seem to capture the crux of it. I am skeptical for several reasons:

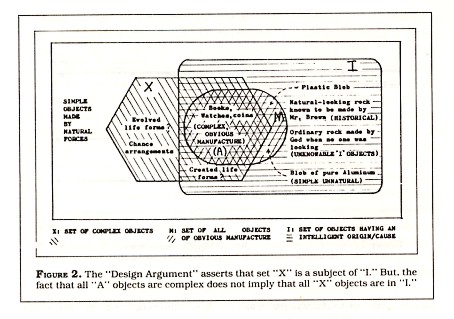

(a) It is not clear that class "I" objects (of which "A" objects are a subset) include DNA. A distinction is to be made between the capabilities of primitive natural forces and the effects of what we call "intelligent cause." This distinction cannot be made without fully understanding the limits of nature. (Wind, ice, and rain may carve many patterns on a mountain, but it is unlikely that the faces of Mount Rushmore would be so produced. Therefore, those faces must have an intelligent origin. On the other hand, if watches were produced within the sands of certain beaches, then we would be hard pressed to say whether or not an unknown watch had an intelligent origin.) Without knowing its history, we cannot place an object in class "I" without first showing that its structure is beyond the range of natural forces. (There is some uncertainty, for example, in assigning an intelligent origin to some of the most primitive "stone tools.") Class "A" objects have all passed the test, but DNA is not a member of that class. The fact that the information content of DNA may be mathematically similar to class "A" objects is irrelevant. We may, however, discuss a class of objects which are defined by complex information content-say class "X." But it does not follow that class "X" is a subset of class "I." (Class "X" is clearly not a subset of class "A," though the reverse is true.) Can nature produce DNA? The only hope of settling such arguments is to dig into the scientific details. I see no easy philosophical shortcut.

(b) Objects with similar structure do not necessarily have similar origins. A nugget of gold may well be natural, whereas an exact duplicate of pure aluminum clearly indicates an intelligent origin. We are dealing with more than abstract information content.

(c) It is not altogether clear to me that the information content of DNA is comparable to a book. I'm under the impression that DNA contains a lot of "junk" or "clutter" which suggests that evolution has played a role. The design hypothesis does not fit well with such evidence.

(d) The term intelligent origin (intelligent cause, nonnatural origin) is not well defined. Are we implying that nature could not create an "intelligent" object in a few million years, or are we saying that a natural creation is flatly impossible? The evolutionist might well claim that even intelligent design (the faces on Mount Rushmore, the works of Shakespeare) is ultimately the product of natural forceshumans being an evolutionary tool of nature. It is not clear to me that "intelligent cause" is exclusive of natural forces. Even if we found a group of stars out in the middle of nowhere spelling "Guess who?" there is no guarantee that its creator or creators must be the first link in the chain of cause and effect.

Dave E. Matson

I feel I have to make one last effort regarding the Geisler articles. Hopefully the following will be of some use to you.

I think all of us who have followed the scientific-theological-philosophical interchanges between Professor Geisler and his antagonists in the past few issues of Creation/Evolution are indebted to him for his efforts and especially for his last letter (Creation/Evolution XVIII) in which he clearly summarizes his position. It is sometimes difficult, however, to understand how people of roughly equal good intentions and intelligence can come to such different conclusions regarding the origin of life on this planet.

After reading and rereading the relevant discussions of those who participated in this important interchange of ideas, I have tried to isolate the fundamental argument Geisler uses to show there was a supernatural, intelligent cause of the origin of life. The argument (briefly summarized) seems to be as follows. Only an intelligence of divine proportions could be the cause of the first DNA since DNA (or similarly complex information systems) are like the intelligence displayed by humans in such things as language, computer design, and so forth. More precisely, since DNA and human information systems are similar in important ways (which we learn from observation), and since language (and computer systems) came about from intelligent design, so the first DNA must also have come about from intelligent design.

It seems clear to me, though, that the weight of this conclusion simply cannot be borne by the premises and for several reasons. First, we have nothing to compare human, complex information systems with other than DNA (or RNA, and so forth). One comparison is simply not adequate for such a weighty conclusion. Such analogical arguments require much more data within the premises to be at all convincing. If we could contact beings on another planet who knew how to make complex replicating systems similar to those life forms here on Earth, Geisler's argument would be much stronger. Unfortunately, we know of no such creatures or their works; we only know what humans have done.

Second, Geisler avoids a key point made by Edwords in one of his rejoinders (Creation/Evolution XVII, p. 41), viz., DNA was not always so complex; there were simpler life forms that used a simpler DNA structure such as in one-celled organisms and viruses. There also exists some rather complex molecular structures that involve complex information systems but are inorganic, such as certain crystals. Where do Geisler and other creationists draw the line between necessary intelligent design of such complex molecules and their information systems and other less sophisticated systems, such as crystals? It seems to me Geisler must argue either that all information systems (complex or simple, living or nonliving) have an intelligent design or that even the most complex of systems have a naturalistic origin. I do not see how he, or anyone else, can convincingly argue that only the most complex, living, replicating systems have an intelligent design but no others. This is not only arbitrary but begs the question of why one must draw the line at A rather than B. (This reminds me of the same kind of question begging point at which many religionists draw the line between humans and nonhumansthat is, at the moment of fertilization of the human ova.)

To claim, as Geisler does, that there is no similar scientific plausibility between information systems of lesser complexity and DNA or Mount Rushmore is to ignore the enormous amount of work done by scientists in the past fifty years or so in uncovering such plausible similarities. As pointed out earlier, there are not a few information systems quite similar to human DNA though not quite as complex as found in lesser creatures or , even in the DNA of viruses and one-celled organisms. To complain that this is still DNA is not legitimate criticism, since the DNA structure found in humans is about as different from the DNA in a virus as is the DNA in a virus from the complexity of a snowflake (although, at present, little is known about the information system of a snowflake). That the former are living things and the latter nonliving makes no difference to the argument either, since degrees of complexity (and inherent information systems) are all that is needed to indicate the required similarities. Thus, we have indirect inductive evidence (the term constant conjunction is pretty well outmoded now, despite Hume's reputation in philosophy) of lesser complex systems leading to more complexity through time. We have no such similar evidence of complex systems somewhat like DNA having been created ex nihilo by intelligent design.

A last criticismand perhaps the strongestof Geisler's argument is that the conclusion can state no more than what is already in the premise. That is, one cannot have any characteristics in the conclusion of an analogy which are not already found in the premises of the argument. Logic isn't magic. Geisler wants to conclude that the designer of "first life" is infinite in intelligence and supernatural. But neither of these characteristics can be found in human information systems no matter how complex. As a matter of fact, in one of Geisler's quotes from Yockey (Creation/Evolution XVII, p. 39), it is claimed that the information conveyed in human language is "mathematically identical" to that of DNA. If this were so, this would make human mathematical powers identical to the divine intelligence (perhaps this makes humans divine?)a conclusion which, I think, would be unwelcome by Geisler and other creationists. By the same token, it would follow that this intelligent cause of life had a material body just as humans do (though, of course, not necessarily like our bodies)a point Geisler seemed to have ignored in my letter in Creation/Evolution XVI (p. 47).

Now, if Geisler would grant me these last two points as concessions, perhaps we would not really be so far apart after all. If he would want to maintain that this intelligent cause of life was some very clever material being with only a bit more intelligence that we humans (after all, DNA is a bit more complex than anything we have created, though not infinitely so) and who probably created life on this planet, then the only difference between our beliefs is that I would claim we do not yet have enough inductive evidence to conclude any such probability. Since we have seen some of the things nature can and has done on its own, I would say. the probability is that nature itself "caused" DNA over countless millions of years; it needed no help from divinity. I would, though, allow the possibility of intelligent design somewhere near the beginning of the development of life.

The other claims made by Geisler in his letter are much less plausible than his claim for an intelligent design of life, so only a few relevant comments will be made here.

Geisler claims that we have a clue for the existence of a supernatural originator of life from the results of science itself. He claims that science has shown that the universe "came into existence" some (fifteen) billions of years ago. He quotes Jastrow's claim that the universe "began abruptly in an act of creation" and that "supernatural forces at work . . . [is] a scientifically proven fact." Science, of course, has proved no such thing, not even that the universe was created. That science could ever prove the existence of supernatural forces is as absurd a statement as I have ever read from a supposedly reputable scientist. The phrase supernatural forces in itself is self-contradictory (if something is supernatural, it is not a force in the scientific sense of "force," and, if it's a force, it can't be supernatural since all known forces are natural) and certainly could never be verified scientifically.

Scientists do not yet know what happened in the fraction of time after the presumed "big bang," so how could they know the universe was created or even that it "came into existence"? This last phrase implies that there was no existence prior to the "big bang." No one yet knows what the situation was at time To (or before), so how can it be said that the world "came into existence"?

Furthermore, the fact that most early scientists believed in an intelligent design of the universe in no way proves that their authority as scientists proves them correct in theology or philosophy. Besides, majority of expert opinion has been shown to be wrong in many cases in past historyfor example, the belief in Earth's flatness, the geocentric hypothesis, the belief in blood-letting in medicine, and so forth. I am utterly surprised at Geisler resorting to such fallacious appeals to authority.

But he continues in this vein by claiming that many modern scientists also believe in a supernatural cause of origin of life here. Perhaps this is so, although I know of no recent surveys which attest to this claim. But it proves nothing for the same reasons suggested above: large numbers prove nothing (beyond what scientists believe) and these scientists are outside of their area of expertise.

But beyond these purely philosophical-scientific criticisms of Geisler's position, I am quite dismayed at the effect this position, and that of creationists generally, can have on the appreciation of science itself. To claim an intelligent design of life ex nihilo is to cool the appetite for a scientific understanding of our complex and fascinating world, especially among youth. Pat religious answers to complex questions regarding life and the cosmos can only dull our creative powers and limit our aesthetic appreciation of the magnificence of our natural world (since it is now second to God, at best). Scientific claims and the method of science soon become viewed as an enemy of religion, as something to be wary of, not to be enjoyed or held as a fascinating challenge to the intellect. In short, creationist thought seems to be at least one of the causes in the apparent decline in interest in the sciences today, since it undermines the principles and method of science, causes distrust of the whole scientific enterprise, and destroys that aesthetic sense of love for the world which is nourished by scientific understanding. "To wonder is to begin to understand," it has been said. I worry that such wonder is being destroyed by the influence of creationist thought.

P. Ricci

If ex-astronaut James Irwin does find pieces of wood on the heights of Ararat in Turkey, and if those pieces of wood show signs of having been shaped and joined together with pith or pitumen, will this be proof that the biblical story of Noah is true, that there really was an ark, that it had ridden the Flood, and that it had come to rest on that mountain range?

Another interpretation of such a find suggests itself if we consider the name Ararat: the meaning of the word in Semitic language is "light of lights." This would mark it as the birth location of the sun in its morning risings for the early inhabitants of the Anatolian plateau.

As mountains sacred in worship of a solar deity, they would be the site of temples erected to house the rites

deemed suitable for such a deity. These rites in all probability included the sacrifice of a variety of animals. Poet and novelist Robert Graves, in The White Goddess, sees certain myths as developing through a process he calls iconotropy, in which a rite or historic occurrence is depicted in some way but the picture is reinterpreted by another people to mean something else.

Thus a picture of a line of sacrificial animals entering a temple to be sacrificed would become a line of animals entering Noah's ark. Thus, any find of James Irwin of hewed timbers could well confirm not an ark for floating on the Flood but a temple built to honor the sun.

Irwin is not a skilled archeologist and is probably untrained in methods of preserving and recording those details necessary to establish dates and other essential data. He seems liable to have the Archimides reaction: to seize the artifact and run down the hill crying, 'I've found it!"

Let us hope that, if he does succeed in finding something to support his idea, he doesn't destroy whatever evidence there would be to test.

Kenneth H. Bonnell