Summary of problems:

There are detailed, testable models of the evolution of dual-opening parabronchi in bird lungs from single-opening alveoli found in the reptilian ancestors of birds. Explore Evolution asks a number of questions about this transition, but then fails to offer students any means to answer any of them, or to discuss how a student or scientist might go about finding answers to these questions.

Full discussion:

Explore Evolution asks its readers:

What would the intermediate forms between the single openings (in-and-out) reptilian lung and a dual opening (flow through) avian lung look like? How would it happen in small yet advantageous steps? Can there even be a transition between a single-opening and a dual-opening system? How would the balloon-like alveoli transform into the tube-like parabronchi? How would the lung maintain function? Would the lung transformation happen before or after the development of air sacs? Would it be before or after the four stage breathing cycle?EE, p. 137

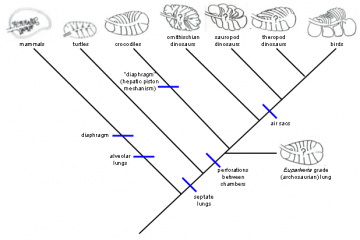

(Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167." title="Lungs of various amniotes, mapped onto the phylogeny of the respective organisms: Mammals are very distant from birds and neither the mammalian diaphragm nor the alveolar lung is thought to be an ancestral character for the lineage leading to birds. The crocodile hepatic-piston method of ventilating the lungs (muscles pulling the liver backwards and thereby expanding the chest cavity) is not homologous to the mammalian diaphragm, and neither basal reptiles nor birds have diaphragms, so it is incorrect to claim that it is "almost certain" that dinosaurs had diaphragms. Perforations (holes) between lung chambers, however, are shared by birds and crocodiles, and thought to be ancestral, so the alleged "topological" problem in producing the bird flow-through lung is imaginary. Sauropods are known to have air sacs from fossil evidence, so air sacs were attached to the lungs of the dinosaurian ancestors of birds for tens of millions of years before theropod dinosaurs and then birds arose. Phylogeny diagram by Nick Matzke. Lungs modified from Figure 1, p. 152 of: Perry, Steven F. (1992). "Gas exchange strategies in reptiles and the origin of the avian lung". Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167.)

Lungs of various amniotes, mapped onto the phylogeny of the respective organisms: Mammals are very distant from birds and neither the mammalian diaphragm nor the alveolar lung is thought to be an ancestral character for the lineage leading to birds. The crocodile hepatic-piston method of ventilating the lungs (muscles pulling the liver backwards and thereby expanding the chest cavity) is not homologous to the mammalian diaphragm, and neither basal reptiles nor birds have diaphragms, so it is incorrect to claim that it is "almost certain" that dinosaurs had diaphragms. Perforations (holes) between lung chambers, however, are shared by birds and crocodiles, and thought to be ancestral, so the alleged "topological" problem in producing the bird flow-through lung is imaginary. Sauropods are known to have air sacs from fossil evidence, so air sacs were attached to the lungs of the dinosaurian ancestors of birds for tens of millions of years before theropod dinosaurs and then birds arose.

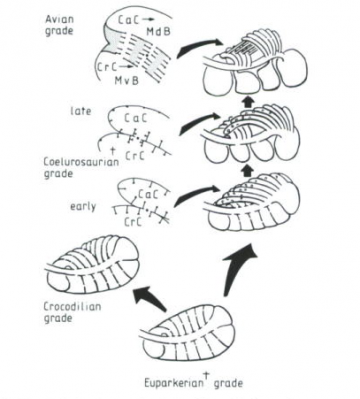

Phylogeny diagram by Nick Matzke. Lungs modified from Figure 1, p. 152 of: Perry, Steven F. (1992). "Gas exchange strategies in reptiles and the origin of the avian lung". Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167.  Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167." title="Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs: Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs, showing the relationship to the crocodilian lung. Archosaur and theropod lungs are hypothetical constructs. Extinct groups are marked with a "+", and perforations between chambers are marked with "*." Perry proposes that these perforations play a crucial role in the stepwise evolution of the avian parabronchi, as indicated in the detail sketches of theropod and avian-grade lungs. CrC and CaC are cranial [forward part of the trunk] and caudal [rearward part of the trunk] chambers, which are connected with the respective regions of the intrapulmonary bronchus. MvB and MdB are avian medioventral bronchi and mediodorsal bronchi, which are proposed to evolve from CrC and CaC, respectively, as indicated by small arrows. From Figure 6, p. 161 of: Perry, Steven F. (1992). "Gas exchange strategies in reptiles and the origin of the avian lung". Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167." class="image image-img_assist_custom" width="360" height="399" />Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs: Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs, showing the relationship to the crocodilian lung. Archosaur and theropod lungs are hypothetical constructs. Extinct groups are marked with a "+", and perforations between chambers are marked with "*." Perry proposes that these perforations play a crucial role in the stepwise evolution of the avian parabronchi, as indicated in the detail sketches of theropod and avian-grade lungs. CrC and CaC are cranial [forward part of the trunk] and caudal [rearward part of the trunk] chambers, which are connected with the respective regions of the intrapulmonary bronchus. MvB and MdB are avian medioventral bronchi and mediodorsal bronchi, which are proposed to evolve from CrC and CaC, respectively, as indicated by small arrows. From Figure 6, p. 161 of: Perry, Steven F. (1992). "Gas exchange strategies in reptiles and the origin of the avian lung". Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167.

Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167." title="Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs: Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs, showing the relationship to the crocodilian lung. Archosaur and theropod lungs are hypothetical constructs. Extinct groups are marked with a "+", and perforations between chambers are marked with "*." Perry proposes that these perforations play a crucial role in the stepwise evolution of the avian parabronchi, as indicated in the detail sketches of theropod and avian-grade lungs. CrC and CaC are cranial [forward part of the trunk] and caudal [rearward part of the trunk] chambers, which are connected with the respective regions of the intrapulmonary bronchus. MvB and MdB are avian medioventral bronchi and mediodorsal bronchi, which are proposed to evolve from CrC and CaC, respectively, as indicated by small arrows. From Figure 6, p. 161 of: Perry, Steven F. (1992). "Gas exchange strategies in reptiles and the origin of the avian lung". Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167." class="image image-img_assist_custom" width="360" height="399" />Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs: Perry's (1992) model for the origin of bird lungs, showing the relationship to the crocodilian lung. Archosaur and theropod lungs are hypothetical constructs. Extinct groups are marked with a "+", and perforations between chambers are marked with "*." Perry proposes that these perforations play a crucial role in the stepwise evolution of the avian parabronchi, as indicated in the detail sketches of theropod and avian-grade lungs. CrC and CaC are cranial [forward part of the trunk] and caudal [rearward part of the trunk] chambers, which are connected with the respective regions of the intrapulmonary bronchus. MvB and MdB are avian medioventral bronchi and mediodorsal bronchi, which are proposed to evolve from CrC and CaC, respectively, as indicated by small arrows. From Figure 6, p. 161 of: Perry, Steven F. (1992). "Gas exchange strategies in reptiles and the origin of the avian lung". Physiological Adaptations in Vertebrates. Wood, S. C., Weber, R. E., Hargens, A. R. and Millard, R. W., Eds. New York, Marcel Dekker: 149 167.

Having asked its audience of high school biology students these detailed questions about evolutionary biology, EE changes topics, without even suggesting the ways that someone might investigate those questions. These students are unlikely to know anything about the anatomy of bird or reptilian lungs, and little if anything about the anatomy of mammalian lungs. They have no experience forming or testing hypotheses about the evolution of anatomical structures, and Explore Evolution offers no references which might fill in that background. The average teacher is likely to be as stymied by these questions as the students. The authors of Explore Evolution seem to be little better informed, and are apparently comfortable leaving students and teachers with no guidance about how to answer the questions posed by the book.

Fortunately, scientists are not so incurious. The figure above demonstrates one set of hypotheses about the evolution of lungs and their anatomy. By considering not just two sets of lungs, but the full spectrum of variation in lung morphology, scientists can reconstruct the likely evolutionary pathways, and evaluate whether those intermediates might be functional.

Scientists like Steven Perry have proposed detailed models of the evolution of the internal lung morphology, models which answer many of the questions Explore Evolution asks. An inquiry-based textbook might describe this model and invite students to develop ways to test it against new data. Instead, Explore Evolution ignores actual research in order to preserve their creationist argument.